Learn about Mechanical Engineer Training

Outline

– Why training matters and how it connects classroom concepts to real machines and systems.

– Core foundations: math, physics, materials, and the mindset of modeling and approximation.

– Practical tools: CAD, simulation, metrology, manufacturing processes, and lab safety.

– Pathways and specializations: energy, automation, product design, and more.

– Experience and credentials: internships, licensure, certifications, and portfolios.

– Future-proofing: sustainability, digitalization, and habits for lifelong learning.

Core Foundations: Math, Physics, and the Language of Machines

Mechanical engineer training begins with fluency in the languages that machines speak: mathematics and physics. Calculus and differential equations teach you how change accumulates and interacts; linear algebra helps you encode systems with many moving parts; statistics equips you to interpret noisy measurements and quantify uncertainty. On the physics side, statics introduces equilibrium and load paths, dynamics captures motion and vibration, thermodynamics explains energy and entropy, and fluid mechanics reveals how pressure and velocity trade places through pipes, ducts, and blades. These topics do not live in isolation; they form a toolkit that lets you model a gearbox tooth, a pump impeller, or a heat exchanger with the same underlying logic.

A solid foundation is not only about formulas but also about habits of mind. The first is modeling: building a simplified representation that keeps essential features and discards the rest. The second is unit discipline: tracking dimensions so that errors are caught before they reach a test bench. The third is order-of-magnitude estimation: answering, quickly and credibly, whether a motor will overheat or a beam will deflect too much. These habits support judgment, the quiet force that separates acceptable from exceptional designs.

Consider examples that make the abstractions concrete. When you design a bracket, you combine statics to determine forces, mechanics of materials to choose a safe cross-section, and manufacturing knowledge to select a process that fits cost and tolerance. When evaluating a small pump, you translate a flow requirement into head, account for losses, and check the motor’s power draw against thermal limits. In thermal systems, you might size a fin array by balancing convection, conduction, and space constraints, comparing analytic approximations with empirical correlations. Tolerance stacks under a fraction of a millimeter are routine in precision devices, and a working knowledge of how thermal expansion nudges those stacks keeps surprises away during temperature swings.

Useful mental tools include:

– Free-body diagrams to visualize forces and moments

– Dimensional analysis to derive relationships before diving into complex math

– Energy balances to connect inputs, losses, and outputs

– Failure modes thinking to anticipate what could go wrong and how it would manifest

With these pillars in place, later topics like control systems and mechatronics become far easier, because you already think in terms of models, feedback, and constraints.

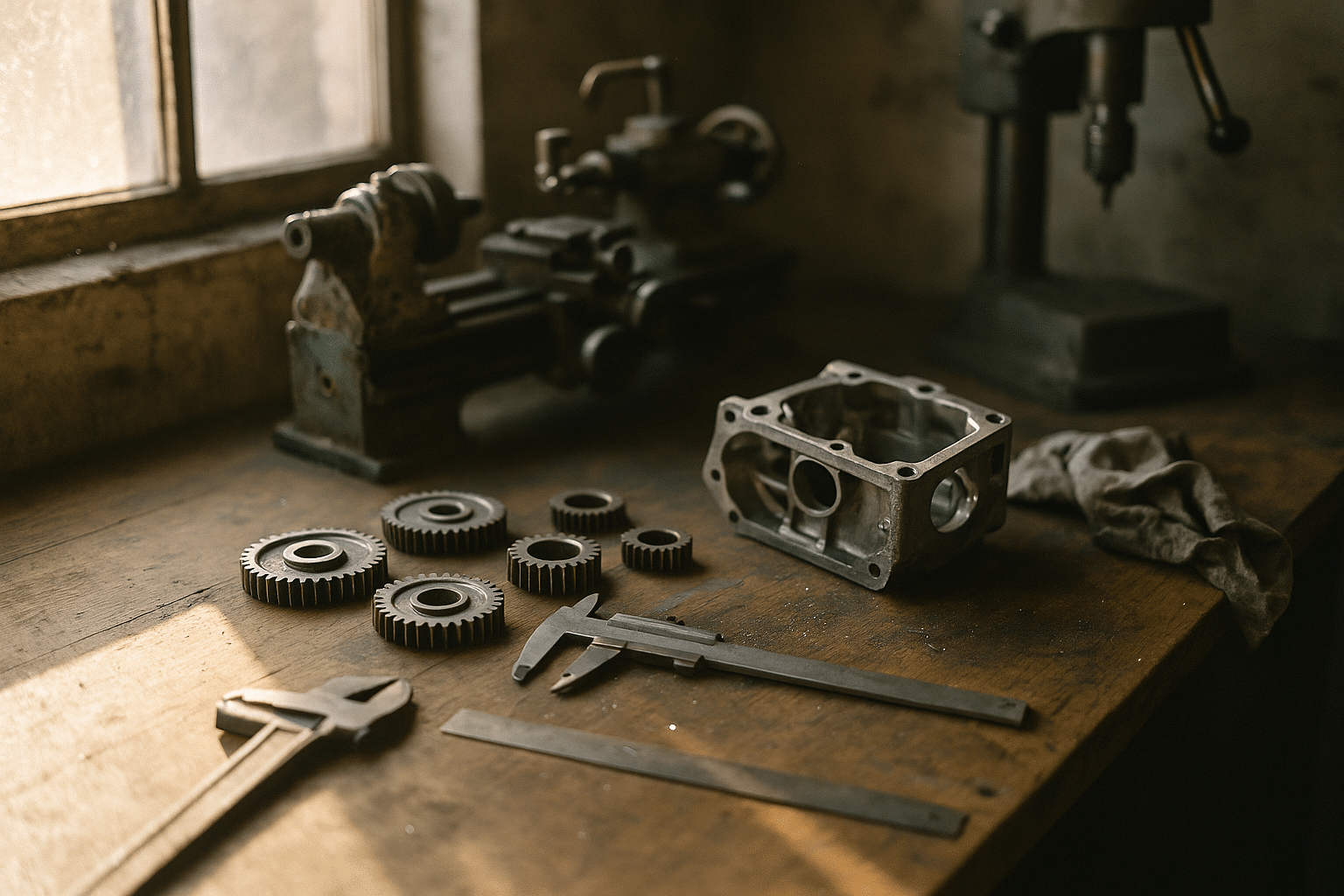

From Theory to Workshop: Tools, Labs, and Digital Skills

The workshop translates equations into parts you can hold, measure, and test. Training typically blends design environments, simulation tools, and manufacturing equipment so you can navigate the full loop from idea to artifact. Parametric CAD lets you define geometry with intent, capturing dimensions and relationships that update when requirements shift. Finite element analysis offers a window into stress, deformation, temperature fields, and vibration, helping you ask better questions before committing to metal. Computer-aided manufacturing converts models into toolpaths, while numerically controlled mills and lathes cut material with repeatable precision. Additive manufacturing brings freedom of geometry, enabling internal channels, lattice structures, and rapid iteration.

Comparisons sharpen judgment:

– Subtractive vs. additive: Subtractive excels at tight tolerances and familiar finishes; additive is agile for complex shapes and consolidation of assemblies.

– Analytical hand calculations vs. simulation: Hand calcs build intuition and set bounds; simulation explores details and interactions, but only as trustworthy as the assumptions behind it.

– Prototyping vs. virtual testing: Physical prototypes reveal real-world friction, fits, and surface effects; virtual tests are fast and inexpensive for exploring many variants.

Metrology is the discipline that confirms a drawing became a part within tolerance. You will learn to use calipers, micrometers, height gauges, coordinate measuring systems, and surface roughness comparators. Geometric dimensioning and tolerancing provides a precise language for form, orientation, and location, ensuring parts from different processes assemble as intended. Instrumentation and data acquisition extend measurement into dynamics: strain gauges, thermocouples, pressure transducers, and accelerometers uncover what happens under load or heat.

Lab culture matters as much as equipment. Safety is nonnegotiable: lockout/tagout procedures protect against unexpected motion, proper guarding keeps hands away from cutting paths, and ventilation controls fumes and dust. Good practice includes clean fixtures, documented setups, and versioned files so results can be reproduced. A short checklist saves hours:

– State the objective and expected outcome before you touch a tool

– Define acceptance criteria and measurement plans

– Record tooling, speeds, feeds, and anomalies

– Capture photos of setups for future reference

By cycling through design, build, test, and revise, you internalize a rhythm that turns theory into dependable hardware.

Pathways and Specializations: Finding Your Engineering Niche

Mechanical engineering is broad by design, and training opens many doors. Some engineers gravitate toward energy systems, working on turbines, heat pumps, batteries, or thermal storage. Others pursue robotics and automation, blending mechanisms, sensors, and control logic to build machines that assemble, transport, or inspect. Product design and consumer hardware reward empathy for the user, elegant mechanisms, and cost-aware manufacturing choices. Mobility-focused roles may tackle powertrains, lightweight structures, thermal management, or noise and vibration. In built environments, you might design heating, cooling, and ventilation systems that keep indoor spaces comfortable with modest energy use. Medical device work emphasizes reliability, biocompatible materials, sterilization, and stringent validation.

Each niche highlights a slightly different skill mix:

– Energy systems: thermodynamics, heat transfer, fluid machinery, and system optimization

– Automation and robotics: mechanisms, kinematics, sensing, control, and safety standards

– Product development: design for manufacturing, ergonomics, materials selection, and lifecycle cost

– Mobility: structures, dynamics, fatigue, tribology, and environmental exposure

– Built environment: load calculations, duct and pipe design, codes, and commissioning

– Medical devices: risk management, cleanroom manufacturing, and verification and validation protocols

Work environments vary, and fit matters. A test lab rewards patience and method: setting up experiments, ensuring calibration, and debugging measurement noise. A design office values clarity: clean models, readable drawings, and reasoned trade-off memos. A manufacturing floor demands decisiveness: fixing a fixture, adjusting a process, or negotiating a tolerance with suppliers. Field roles cultivate resilience: diagnosing issues in real installations, where dust, temperature swings, and wear test your design’s assumptions. Across all settings, the ability to communicate with multidisciplinary teammates is essential; many projects span electrical, software, and operations, and mechanical engineers often act as integrators who keep the whole system coherent.

Training programs and early projects are good places to sample these paths. Rotate through lab work, design sprints, and shop time to see what energizes you. Keep a log of tasks that felt intuitive and tasks that drained focus; patterns will appear. When a domain resonates, study its standards, typical failure modes, and signature constraints; those anchors let you contribute meaningfully faster and help you spot hidden risks in reviews.

Experience and Credentials: Internships, Licensure, and Certifications

Real-world experience transforms classroom knowledge into professional competence. Internships and co-op placements expose you to the pace, priorities, and constraints of engineering teams. You might update a test rig, analyze production scrap, rework a drawing for improved manufacturability, or help instrument a prototype for a fatigue test. Each task, however small, is a chance to practice requirements gathering, communicate progress, and close the loop with data. A capstone project can serve as a bridge: scoped with a sponsor, reviewed at milestones, and judged by whether it meets explicit criteria under budget and schedule limits.

A strong portfolio accelerates your early career. Include a brief problem statement, the approach you chose, alternatives considered, and measurable outcomes for each project. Photos of prototypes, annotated test plots, and side-by-side comparisons of design iterations help reviewers see how you think. Quantify impact when possible: reduced cycle time, improved yield, lighter mass, lower power draw, or tightened tolerance leading to fewer defects. If you worked in a team, clarify your role, decisions you owned, and how you handled interfaces with other disciplines or suppliers.

Credentials add structure to growth. Many jurisdictions offer engineering licensure, typically requiring a recognized degree, foundational and professional exams, and supervised experience. This path is especially relevant when you sign off on public safety-related work or provide services directly to clients. Beyond licensure, targeted certifications can validate skills that employers value:

– Quality management and auditing credentials for roles focused on compliance and process improvement

– Project management certifications for planning, risk, and stakeholder coordination

– Safety and reliability certificates for hazard analysis and maintenance planning

– Additive manufacturing or machining credentials that demonstrate process-specific competence

Networking and references matter, but they are built on substance. Seek mentors who will review your designs critically and explain their reasoning. Volunteer for tasks that touch constraints you have not yet mastered: cost modeling, supply chain, or environmental compliance. Keep a learning log of failures and fixes; being able to articulate what went wrong, why, and how you prevented recurrence is the kind of professionalism that hiring managers remember. Over time, experience, evidence, and credentials weave into a reputation for reliability.

Future-Proofing: Trends, Sustainability, and Lifelong Learning

The tools and constraints of mechanical engineering evolve, and training is only the opening chapter. Digital models are becoming living assets that persist from concept to service, and simulations are increasingly used alongside physical tests to shorten cycles. Data streams from sensors inform design updates and maintenance, while automated optimization explores design spaces faster than human iteration alone. None of this replaces engineering judgment; it amplifies it, provided you understand the assumptions, limitations, and failure modes behind the numbers on the screen.

Sustainability is reshaping design choices. Energy efficiency is one pillar, but the picture is larger: materials with lower embodied impact, designs that enable repair and remanufacture, and systems that minimize waste over decades of use. Lifecycle thinking helps you compare alternatives beyond the purchase cost, considering service, disposal, and potential secondary use. Practical steps include:

– Selecting alloys and polymers with documented environmental profiles and reliable supply

– Designing joints for disassembly so parts can be replaced or reclaimed

– Right-sizing motors, pumps, and heat exchangers to realistic duty cycles

– Reducing over-tolerance that drives unnecessary machining time and scrap

These decisions are often modest on their own, but together they compound into measurable gains for both cost and impact.

To keep skills fresh, build habits that survive busy schedules. Set quarterly themes, such as advanced failure analysis, modern control techniques, or a new manufacturing process, and pair them with a small project. Read standards and application notes in your niche; they capture lessons learned across industries. Join professional communities where engineers share postmortems and practical tips. Maintain a sandbox where you test ideas quickly: a desktop test rig, a small 3D printer, or a simple data acquisition setup. Most importantly, practice clear communication. A concise memo that explains a trade study, cites data, and recommends a path forward is often the lever that moves a program.

Conclusion for trainees: mechanical engineer training is not a checklist; it is a method. Learn to model, measure, and make. Seek feedback, embrace constraints, and focus on decisions that reduce risk early. If you invest in foundations, practice in the workshop, explore a niche, and adopt a learning rhythm, you will be equipped to design systems that work the first time they meet reality—and improve them every time after.